As the University of Malta’s Electronics Systems Engineering Department works on sending the first Maltese satellite into outer space, Dr Ing. Marc Anthony Azzopardi explains the process and the benefits of such an accomplishment.

The frontiers of science and technology are constantly being pushed forward, giving us a better understanding of the world we live in, and better ways of manipulating the elements that make it up. As time goes on, those advancements are taking place more often and at a faster rate than ever before. But where does Malta fit into the great scheme of things?

The frontiers of science and technology are constantly being pushed forward, giving us a better understanding of the world we live in, and better ways of manipulating the elements that make it up. As time goes on, those advancements are taking place more often and at a faster rate than ever before. But where does Malta fit into the great scheme of things?

For anyone who has followed this blog from the beginning, it will come as no surprise when we say that Malta is definitely a player in the world of research and medical innovation. For a country that is a fraction of the size of most European capitals, the potential that is being unlocked is astonishing.

Yet one area that has often been overlooked – most probably because many people assumed we’d have no luck in it – is space and everything related to it, including satellites and space exploration.

But all that is set to change as the University of Malta’s Faculty of Engineering is finally working towards sending the first Maltese satellite to space by 2018!

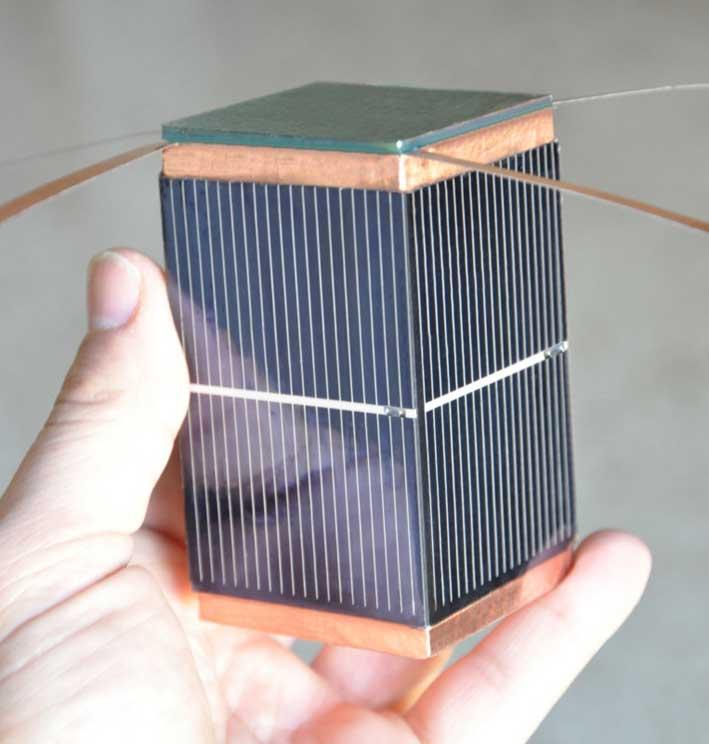

“The idea came to me while at a conference in Seattle back in 2011,” says Dr Ing. Marc Anthony Azzopardi, a lecturer and researcher within the Electronics Systems Engineering Department of the UoM. “It was there, at the DASC Conference, that I first saw nanosatellites and picosatellites built from little more than a mobile phone motherboard.

“As you can imagine, that is by no means a straight forward thing to do as all components within a satellite need to be able to resist oxidation, intense ionizing radiation, and even severe swings in temperature. In order to ensure that the satellite we’ll be sending can withstand the abnormal (by earthly standards) conditions, we have had to test hundreds of different components under extreme conditions.”

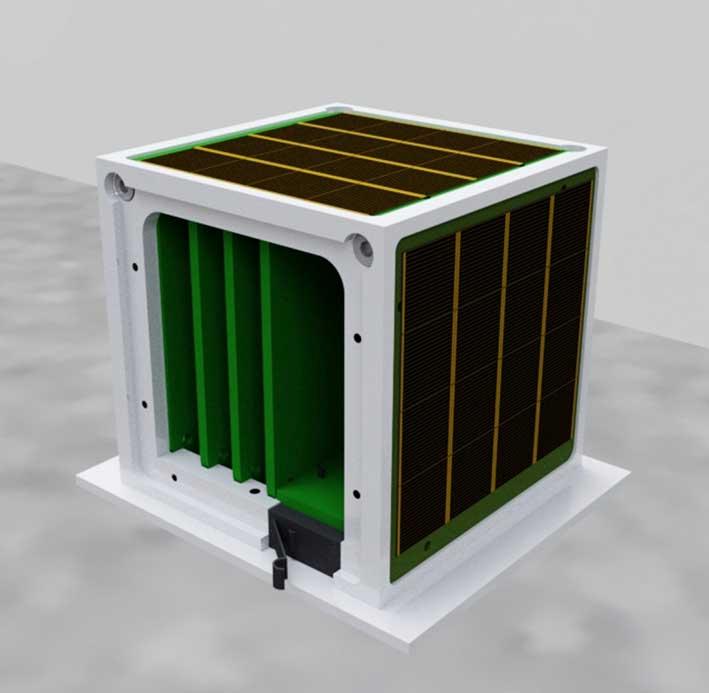

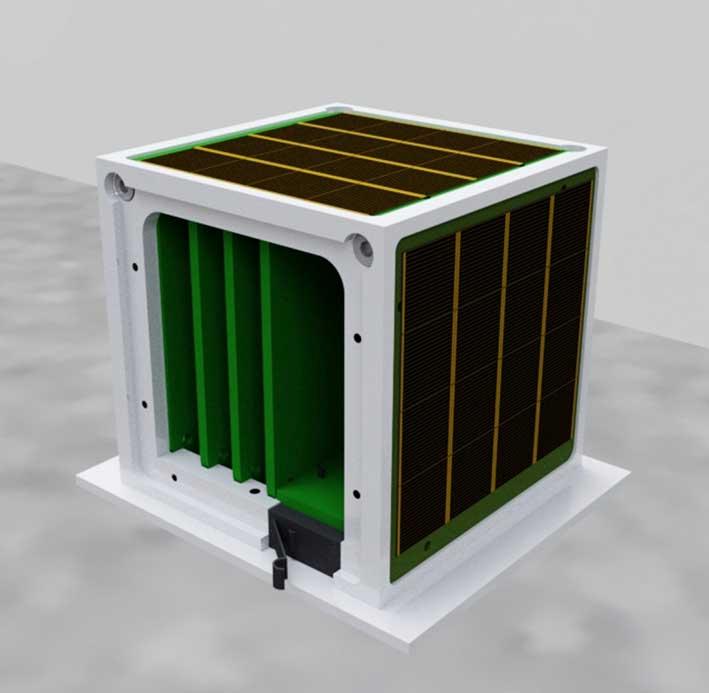

3D Model of UoMSat1 – the University of Malta’s first Pico-Satellite

The hardware will cost just over EUr 30,000 to complete, so a technology demonstrator (aka prototype) will be sent into space to allow Dr Azzopardi and his team to test the basic systems, and hence propose improvements for more ambitious missions.

The final device, which has been nicknamed the ‘UoMBSAT1’, will also carry a payload (a module housed within the satellite but that works independently), which will be monitoring certain characteristics of the earth’s ionosphere. It’s good to note that the payload is being created by Jonathan Camilleri, a PhD student who is currently working in Birmingham under the expert guidance of Prof. Matthew Angling. This Malta‑Birmingham collaboration is pivotal to the success of the satellite, hence the ‘MB’ in the name of the satellite.

“Jonathan’s project is an Impedance Probe, which will test the properties of the top side of the atmosphere, called the ‘ionosphere’, which is an electrically-charged layer. This layer, which protects us from radiation – literally, without it there would be no life on earth – also affects radio waves, meaning it messes with readings when scientists are conducting radio astronomy [the study of celestial objects at radio frequencies], or when trying to do earth observation from satellites using synthetic aperture radar.”

Through the satellite and the Impedance Probe, Dr Azzopardi and the rest of the team will be testing software to measure the ionosphere in real-time, potentially leading towards a reality in which this could be compensated for. Should this be successful, it would allow for scientists the world over to obtain more accurate data, and take clearer pictures of the earth.

Working on this with Dr Azzopardi is Darren Cachia, the first student to apply for a Master’s degree in Astrionic Systems Engineering at the UoM. Darren’s studies are being sponsored by the Endeavour Scholarship Scheme, which are partly funded by the EU, and his job is to design the top system architecture of the satellite along with the sub-system.

“When designing, there are a lot of things you need to keep in mind,” Darren explains. “You have to set requirements for everyone, whether they’re working on the physical parts of the satellite or on the software.”

An early mock-up demonstrating the typical size of a Pico-Satellite

Darren’s job, in a nutshell, is to work on the on-board computer system for the UoMBSAT1 and its power supply, as well as the attitude control system that will help the team control the way it’s facing – an important task to ensure it functions properly, and continually gets information about the ionosphere.

“The team is ever changing, however, and we have people coming down from Switzerland, Turkey, France and Croatia this summer to help with the various systems,” continues Dr Azzopardi. “At the moment, aside from all the students working on this project, there are 12 academics – and the total number of people working on this will go up to 30 by the summer.”

For this particular satellite, the Electronics Systems Engineering Department is also working closely with the Universita di Sapienza di Roma, which will be launching its seventh collection of satellites this December.

“Once it’s complete, the satellite will be launched from one of the existing spaceports somewhere in the world, most probably the one in Kazakhstan. The satellite, however, is too small to be sent to space by itself, so it will hitchhike a ride there on a larger satellite,” he adds.

Among the many challenges being faced by the UoM in the lead-up to the completion of this satellite, is the fact that, as it stands, it would take the satellite 170 years for it come back to earth. This is mostly due to its size, weight and the velocity it will be travelling at, yet International Space Law states that no satellite should orbit the earth for longer than 25 years.

Even so, Dr Azzopardi and his team are adamant that they want to make this dream a reality, and give Malta a chance to shine even out in the cosmos. Will they succeed? We think so!

Watch the previous Launch of UniSat-6 Nano-Satellite Cluster by GAUSS Srl. in June 2014

You too can be part of this fascinating world of research by supporting researchers in all the faculties of the University of Malta. Please click here for more information on how to donate to research through the Research Trust (RIDT).