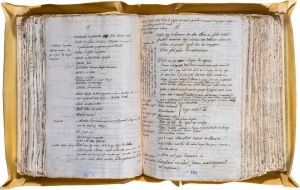

Written 248 years ago, De Soldanis’s Manuscript is not just a Maltese-to-Latin-to-Italian dictionary, but the immortalisation of the world in which Canon De Soldanis lived. Here, Olvin Vella, assistant lecturer at the Department of Maltese at the University of Malta, gives us insight into De Soldanis’s world, as well as into the ongoing work that will make this rare and unique manuscript available to the public.

Can you imagine what life was like in the Year of Our Lord 1767? Well, for starters, there was no modern technology, as industrialisation was still in its infancy. People were very superstitious, and religious references and icons would have been omnipresent. More than that, our collective knowledge was still very limited – in fact, we didn’t even have a map of the eastern coast of Australia yet.

Can you imagine what life was like in the Year of Our Lord 1767? Well, for starters, there was no modern technology, as industrialisation was still in its infancy. People were very superstitious, and religious references and icons would have been omnipresent. More than that, our collective knowledge was still very limited – in fact, we didn’t even have a map of the eastern coast of Australia yet.

The most surprising thing, however, is how little we’d have cared for any of the above. Without social media and with widespread illiteracy, life for many revolved around their parish and livestock, with a rare trip to the capital being the only way of escaping the daily grind for a few hours.

Gian Piet Agius de Soldanis was different, though, and, in a world in which illiteracy reigned, he had mastered the pen; and in a world in which most people never traveled far from home, he left our shores for years at a time. All this is made even more awe-inspiring by the fact that De Soldanis was a Canon from, and who lived in, Gozo – which was far less connected to the outside world than it is now.

“The man was brilliant,” says Olvin, who, as assistant lecturer at the Department of Maltese at the University of

Malta, has been overseeing Rosabel Carabot and Joanne Trevisan on their mission to publish the De Soldanis Manuscript. “Yet, throughout his life, he always felt like he was surrounded by farmers and hunters.

“That’s why, whenever he went abroad, he felt like he was being set free,” he continues. “In one instance in the manuscript, we discover that he went on a grand tour for two years to travel around Italy and France – this is something very few Maltese and, indeed, Gozitans, at the time could boast about.

“While there, De Soldanis met many interesting people and spent time in some of Europe’s most buzzing cultural centres, too. This, undoubtedly, helped shape his unique pen and sense of humour.”

De Soldanis’s manuscript, in fact – although, technically, a dictionary of now-old Maltese words – is actually more of a journal and a lexicon of a language that was changing and evolving incredibly quickly.

At the point in time which De Soldanis was writing his magnum opus, Malta was still under the rule of the Knights of St John – it would be another 31 years before the French would invade Malta, and another 33 before the British would be called in. This, as one can imagine, means that this dictionary gives us an insight into the words that were used then and, coupled with de Soldanis’s comments and notes, opens a door to a world rarely seen in history books – that of the lower classes.

“Through this book we know that ‘gverti’ (throws) made out of sheep’s wool were exported to the continent, and that the sacramental bread was called either ‘ostja’ or ‘xawwata’ – the latter being the same name used for a ‘ftira’.

“Even more interesting is that we know that they had two words for the verb ‘to wash’, for example. These were ‘jixxalakwa’ from the Italian ‘risciacquare’ and ‘jahsel’ from Arabic. We also know that a peacock, which today we’d call ‘pagun’, was then called a ‘taus’ but translated to Italian as ‘pagone’.”

De Soldanis goes even further than that, however, and explains how an ‘ghawwiem’ (a swimmer) is someone who swims, and that women from Isla were as good at swimming as the men. L-Imnarja, on the other hand, is not just the Feast of St Peter and St Paul, but a day on which people go out to get drunk and go to church. The reader is also told about Favray’s painting of the Mnarja, and that the feast is celebrated in Nadur, Gozo.

De Soldanis goes even further than that, however, and explains how an ‘ghawwiem’ (a swimmer) is someone who swims, and that women from Isla were as good at swimming as the men. L-Imnarja, on the other hand, is not just the Feast of St Peter and St Paul, but a day on which people go out to get drunk and go to church. The reader is also told about Favray’s painting of the Mnarja, and that the feast is celebrated in Nadur, Gozo.

“It is this unparalleled insight into the world of 250 years ago that was worth all the work that Rosabelle Carabot and Joanne Trevisan have gone through,” Olvin explains. “For hundreds of years, this book has been locked up in the National Library, with very few people actually leafing through its pages.

“Now, through its digitisation, the book will be able to be printed and used by scholars, historians and even those who are interested in learning more about the way our ancestors thought and lived,” he adds.

The project to create a mass-market copy of De Soldanis’s monumental manuscript has been in the works for over six years, and it is expected to go on sale in 2016.

“A special thank you should also go to the National Library, which allowed us to use digital versions of the document to facilitate our work. And, obviously, RIDT and Wilfred Kenely, for their constant support,” Olvin

concludes.

The book, which will be around 1,000 pages long, has been funded by BPC International Ltd through RIDT, l-Akkademja tal-Malti, il-Kunsill Nazzjonali tal-Ilsien Malti and Heritage Malta. The transcriptions are by Rosabelle Carabot and Joanne Trevisan, with the former also in charge of editing and revision. Daniel Cilia has been entrusted with the design and publication.

De Soldanis’s manuscript will be available for pre-order at this year’s Book Fair in November.

4 Comments

-

I would like to order one as soon as possible, possibly before the November book fair?

Thank you.-

Author

I have forwarded your request and will be contacting you shortly if it is possible to pre-book before the November book fair.

-

-

Prosit lil kull min hu involut.